Who Killed the Iguanas?

John Woram

Originally appeared in Noticias de Galápagos, No. 50, 1991.

Popular wisdom has it that no iguanas remain on Baltra because American troops used them up for target practice during World War II. It's a believable legend: imagine being barely 20 years old, newly drafted and sent to a place that could very well be the next Pearl Harbor. You have nothing to do but stand around and wait for something terrible to happen. But of course, nothing terrible does happen. In fact, nothing happens, period. It will take about 20 more years until the Charles Darwin Research Station is born and the world wakes up to the non-military significance of this God-forsaken place. But in the meantime, your home so far away from home is just “The Rock,” a term of endearment formerly reserved for Alcatraz, another prison watched over by gun-toting guards. But on this rock, the guards are also the prisoners, for there's no ferry service back to more congenial surroundings at the end of each boring day. So you pass the idle moment by taking a few shots at some stupid lizards. So the story goes.

But eventually the war does end and everybody gets to go home. Some years later scientists arrive and note the absence of land iguanas. They recall the island was occupied by American troops during the big one and set down the following observations:

- Iguanas were here before the war,

- Americans were here during the war,

- iguanas are missing after the war.

This leads to the obvious conclusion: the Americans killed all the iguanas. In due time hypothesis becomes theorem, and today there's hardly a wildlife study or discussion of the island that does not include the obligatory “senseless slaughter” reference. Despite the absence of a single first-hand account, the hypothesis is so believable that it passes unchallenged. It's almost as though we expect young men to do such things. And so the American troops are judged—in absentia and without trial—guilty.

Perhaps the judgment should be appealed, if not on the basis of newly-found evidence, then at least on re-examination of the old; specifically, World War II records now preserved on microfilm at the United States Air Force Historical Research Center at Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, supplemented by information from the archives of the Smithsonian Institution and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library at Hyde Park, New York. By studying these documents it's possible to reconstruct—at least partially—an account of what did, and what did not, happen to the iguanas during the war.

The earliest reported use of Baltra by American forces was as a seaplane base, starting on January 6, 1942, with construction of a runway beginning in February (Panama Canal Dept. 1946). Before the first plane could land, wildlife warnings had already been heard in Washington. Dr. Waldo LaSalle Schmitt, curator of the Smithsonian Institution's Division of Marine Invertebrates, took advantage of his acquaintance with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to sound the alarm. In 1938, Schmitt was part of the presidential cruise to Galápagos aboard the U. S. S. Houston. And now, knowing of the president's continuing personal interest in the islands, Schmitt wrote him on March 4 to warn of a “… great danger that the iguanas, both land and marine, which are no longer very plentiful, may be made the objects of target practice.” He continued with the suggestion that the hunting of goats and other feral animals be encouraged (Roosevelt 1942). A month later, the first plane landed, followed by the arrival of an Army contingent on May 9 (Panama Canal Dept. 1947, pp. 9 & 24). Within the next two weeks, the commanding officer of the brand new Army Air Base, Colonel William Gravely, distributed a memorandum to draw attention to the status of the islands as a game preserve. The May 20 memorandum stated that the “The killing of all animals and birds is prohibited” (Johnson 1942).

A few weeks later, the Smithsonian's Assistant Secretary Dr. Alexander Wetmore directed Dr. Schmitt to proceed to Galápagos to investigate the possibility of establishing a small laboratory adjacent to the Navy facilities (Wetmore, 1942a & b). This time, his cruise would be somewhat less than presidential; after a five-day voyage out of Panama, the tuna clipper Liberty dropped Schmitt on Baltra—now code-named Base Beta—on Thursday morning, June 25th. He returned to the mainland by plane on Saturday, June 27. In his July 7 report to Dr. Wetmore, Schmitt noted that:

Some sections much favored by [the iguanas] have been completely denuded of all vegetation in the course of land leveling operations. The goats and remaining iguanas have been driven into, or concentrated in, perhaps half the range that they formerly occupied. Thus, the animals come into closer competition for food. … Due to the indiscriminate use of pistols during the early phases of the military occupation, so many iguanas were killed that a severe epidemic of carrion flies resulted. [But] this, of itself, brought about some degree of protection, in order to eliminate the pest of flies (Wetmore 1942b).

Unfortunately, Schmitt's report does not elaborate on this, but we do know the remark about the pistols was not based on personal observation. For in his diary (Schmitt 1942) he wrote “Army killed iguanas with pistols, & let carcasses die … I guess [this] made a bad flie [sic] pest.” However, this entry was made on June 15th—ten days before he arrived in Galápagos. By the time he actually got there he was able to jot down a cheerier note: “Killing of animals [is] out,” perhaps as a result of Colonel Gravely's order (June 26 entry, but misdated June 25). But in any case, the Smithsonian didn't want to take any chances on the future. The following excerpt is taken from a November 20 memorandum to the State Department, signed by Dr. Wetmore:

It is recognized that disturbances through construction and actual occupancy are unavoidable, but it is important and necessary that all hunting for game or sport, and all other unnecessary molestation of the wild life be controlled and prohibited by the military authorities … . Should any [animals] be destroyed needlessly, much resentment inevitably will arise (Wetmore 1942c).

On December 9, 1942, Wetmore's memorandum was forwarded to the Commanding General, Caribbean Defense Command, along with a directive, by order of the Secretary of War, that

… you take appropriate action to prevent any unnecessary molestation of the wild life in the Galapagos Archipelago and to prohibit the introduction of domestic animals that may prey on the native fauna (Daily 1942).

Action was also needed on another front: during a brief visit to Washington, Commander J. J. Gest told Dr. Schmitt of “native laborers killing iguanas for their skins, but he put a stop to it so far as he was able” (Wetmore 1942d). Again, the Smithsonian alerted the State Department:

We have report of native laborers engaged in various work on the islands killing iguanas for their skins. This was stopped by one of the officers but may begin again at any time (Wetmore 1942e).

Both the State Department and the Smithsonian were aware that interested foreign agencies were monitoring the situation and could be expected to take action if the United States permitted the Galápagos habitat to deteriorate needlessly (Wetmore 1942e & f). To say nothing of monitoring by the president himself, who throughout the war always found a little time to urge the preservation of the Galápagos as an international park. In a memo to the Secretary of State, he wrote “I have been at this for six or seven years and I would die happy if the State Department could accomplish something [to persuade every country from Canada to the Straits of Magellan to get behind the idea]” (Roosevelt 1944).

In short, the protection of flora and fauna was taken very seriously, even to the point of interceding in the actions of the civilian labor force.

But could the servicemen themselves be expected to take their orders as seriously as did their president and the Smithsonian? In retrospect, perhaps they took them a little bit too seriously. For example, the orders made no distinction between endemic and feral animals—an unfortunate loophole that the island's goats used to their advantage. A two-column headline in a 1945 edition of the base newspaper ominously reported that

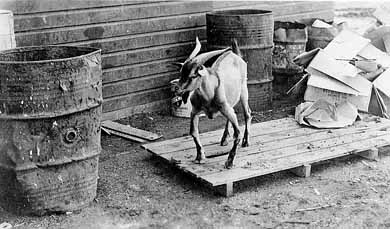

GOATS MAY BE BANNED FROM PX BEER GARDEN

It seems that some (human) newcomers had complained to the PX officer about the presence of the beasts, much to the disgust of the old-timers, who regarded the goats as fixtures. No action was taken, pending further study of the matter (Goat's Whisker 1945). And so, along with their PX privileges, the animals prospered under a well-intentioned but misguided Uncle Sam. Alas, Schmitt's early recommendation to encourage goat hunting had apparently not reached the island. And as a result, a 1946 inspection report from Major-General Harmon to the Chief of Staff noted that

The large number of native goats, protected by Executive Order, make a continuous practice of upsetting garbage and trash cans. They are a great annoyance and a menace to sanitation. Initiate request … for authority to round them up and transport them either to Little Seymour [i.e., Seymour Norte] or to Santa Cruz Island (Harmon 1946).

|

|

|---|---|

| Above: “Billy Bender” Right: Dr. Edwin Rowe and a young patient (photo courtesy of Dr. Edwin Rowe). |

When not raiding the trash cans or drinking with their army buddies down at the PX, the goats had the unsettling habit of wandering (staggering?) across the runway at the most inconvenient moments, and at least a few landings had to be aborted on their account. But such close calls notwithstanding, it would seem that troops and herds lived in more-or-less peaceful coexistence, with the prohibitions against harming the wildlife still in effect.

But what of the iguanas, which is after all the subject of this inquiry? Is it likely that the troops would cheerfully spare the goats yet systematically risk official displeasure by taking on the iguanas? The evidence, such as it is, suggests not. For whatever else the airmen did to pass their leisure time, they took pictures, some of which came to light recently as the result of the following chain of events.

In 1988, a veteran of the 29th Bombardment Squadron revisited the site of his wartime service. Former United States Army Air Force navigator Allan Beucher arrived aboard a Boeing 727, a far cry in time and technology from his earlier flights here in a Consolidated B-24 Liberator. His squadron had operated from Baltra during the period from May 1943 to April 1944 and again from May 1945 through the end of hostilities. During the inevitable wait for the bus to the dock, Beucher reminisced out loud about his tour of duty and was overheard by a local guide who said for all to hear “Oh, you're one of those Americans who murdered our iguanas” (Beucher, personal communication).

Beucher, who had no idea what the guide was talking about, recalled the unpleasant incident a few days later while visiting the Darwin Research Station. While there, Ms. Gayle Davis-Merlen explained the cause of the guide's hostility, and Beucher protested vehemently. A month or so later, I arrived looking for help with the human history of Galápagos. Gayle recalled her recent meeting and gave me Allan's address. When we met I found him still angry about his encounter. By happy circumstance the 29th was planning a reunion (their third) for June of 1989, and a member mailing list was available. We quickly collaborated on a questionnaire in which the squadron members were challenged to dust off their memories and try to answer a few questions: Do you have any recollection of the iguana population when you arrived? when you left? While you were there, did the population increase/decrease/remain stable? Did you see any young iguanas? Do you have any first- or second-hand accounts of hunting iguanas, or of eating them?

Within a few weeks we received 24 responses to the 98 questionnaires we mailed out. The respondents were unanimous: although some recalled taking shots at sharks and rays in Itabaca Channel, as for the iguanas, all denied anything more sinister than occasionally picking one up by the tail, trying to stage iguana races (unsuccessful) and iguana fights (ditto).

| Lt. Nelson and friend. |  |

|---|

At this late date, most respondents were uncertain about population fluctuations, though none recalled seeing any young iguanas. Many said that the only hunting they did was with their cameras. Some had tasted iguana at Rio Hato in Panama, but none had done so in Galápagos. However, one respondent did recall seeing a single iguana that had been shot. He reported that this was an isolated case, and definitely not the norm.

Our little survey is certainly not the last word in scientific inquiry, and perhaps some will discount it for its obvious flaws. But, given the maturity that comes with the passage of almost a half-century, we would have expected a few remarks like “Well of course we took a few shots at the damned animals. What would you expect from a bunch of kids?” Instead, we received a unanimous rejection of the very concept, followed by no shortage of angry comments at the subsequent reunion in June when the squadron members learned the full extent of the legend that has become part of Galápagos folklore.

At that reunion, many squadron members brought along their scrap books full of pictures of their buddies, of the planes they flew in, and of course, of the ubiquitous iguanas. The pictures have one thing in common; the iguanas are reasonably plentiful, and all are quite large. Although there's no shortage of baby goat pictures, there's not one juvenile iguana to be seen. The same general situation was also noted by others stationed on Baltra. Dr. William Kennon was attached to the base hospital from August 1943 to March 1944. In a recorded interview he recalled that

There were plenty of land iguanas. I never recall seeing or hearing of anybody deliberately killing one. Someone who acted as though he spoke with authority said, ‘You know, you only see large iguanas here on The Rock. You never see any small ones.’ After that I specifically noticed the size of the iguanas that we had, and all of them were fairly large (Kennon 1981).

| Not exactly a tiger by the tail, but . . . (photo courtesy of Dr. Edwin Rowe). |

|

|---|

Now, who (or what) do you think was killing off all the young iguanas while sparing their elders? It could hardly be the work of bored humans, who if so inclined would surely find the larger ones—to say nothing of the goats—far far more attractive targets. And whatever the cause of the missing young, its effects had been observed long before World War II. William Beebe noted it in 1923 (Beebe 1924). Some ten years later the members of the Hancock Expedition observed that the iguanas were not thriving on Baltra and transported some of them to Seymour Norte (Banning 1933). Still later, Dr. Loren P. Woods visited Baltra with the Leon Mandel Galápagos Expedition, and it was remembered that “when he visited Seymour in 1940, prior to the establishment of the military base, he found only a very few Land Iguanas—all of them large adults” (original italics, Dowling 1964). And even as Dr. Schmitt prepared for his 1942 trip, he noted to himself that “Young land iguanas seem never to have been taken [on Baltra]” (Schmitt 1942, p. 1).

Base Beta was formally turned over to the Ecuadorian authorities on July 1, 1946, by which time the American forces had been withdrawn, save for a small contingent which remained at the request of Ecuador. Apparently, a contingent of goats remained as well, for Time Magazine reported that during the transfer ceremony, “Galápagos goats idled nearby” (Time July 15, 1946).

With all of this offered for consideration, it would seem grossly unfair to continue blaming the American troops for a phenomenon that had been at work long before their arrival. To be sure, the heavy construction work, with subsequent air and road traffic, took a heavy toll on the surviving adults. But even this did not totally finish them off. For in January 1954, Dr. Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt (1960) reported finding an iguana carcass on Baltra. He writes “The sun had shriveled up the creature's body but still I could make out from the bullet holes that the lizard had been shot.” After noting that the island had made life miserable for so many bored troops, he generously adds that “… we really cannot blame them for what they did.”.

But we have anyway, even though they didn't do it. For if American troops had indeed exterminated the last iguana prior to July 1, 1946, where did the one discovered in 1954 come from? How long had this unfortunate creature baked in the sun before Dr. Eibl-Eibesfeldt discovered it? One year? Two years at best? At risk of stating the obvious, it would seem that the very existence of an iguana carcass in 1954 is sufficient evidence that the American troops have been the victims of an ungenerous press.

As for the last iguana, whether it died in competition with a goat, in the jaws of a feral dog now also gone, or because of reproductive failure is not yet known. But since a few descendants of the original population do live on at Seymour Norte or in the CDRS breeding program, there is now the possibility of re-introducing land iguanas to Baltra. But first, knowing that their recent disappearance was not entirely due to bored American soldiers provides a stimulus for carefully examining all other possibilities, in search of the real truth. The eventual discovery of the cause of their demise may help us (and them) to prevent history from repeating itself.

A 2016 POSTSCRIPT: Despite the passage of some 25 years since the above was first published, some “authorities” have still not “gotten the word” about the adventures of the iguanas, as witness this little bit of nonsense found on—of all places—the Galápagos National Park website (!)

.The Baltra iguanas: rescued from extinction

The land iguana population of the small island of Baltra, north of Santa Cruz, had been considered extinct in 1954, presumably eliminated by U.S. soldiers stationed at the military base that operated on the island between 1941 and 1945.

However, in the early 1930s, the American tycoon William Randolph Hearst took a small population of iguanas to North Seymour, an even smaller island a few hundred meters [actually, about 1,500 meters] from Baltra.

Hearst´s iguanas survived and were the basis for subsequent breeding and repatriation to Baltra. At the moment 450 iguanas have been repatriated to the island.

Needless to say, there is no known record of William Randolph Hearst ever visiting Galápagos, and the transfer of land iguanas to North Seymour was the work of G. Allan Hancock, as described in “That First Iguana Transfer.”

| References | ||

|---|---|---|

| Banning, George Hugh | 1933 | Hancock Expedition to the Galapagos Islands, 1933: General Report. San Diego: Zoological Society of San Diego. Bulletin No. 10 (May). |

| Beebe, William | 1924 | Galápagos: World's End. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. |

| Daily, John R. | 1942 | War Department letter AG 680.25, December 9. USAF Historical Research Center, Reference Division, Maxwell Air Force Base, Microfilm reel 32953. § |

| Dowling, Herndon G. | 1964 | “Goats and Hawks—A New Theory of Predation on the Land Iguana.” Animal Kingdom 67:2 (April), pp. 51-56. |

| Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Irenäus | 1960 | Galapagos. London: Macgibbon & Kee. |

| Goat's Whisker (U. S. Army newspaper published on Baltra) | 1945 | Vol 2, No. 23 (June 19), p. 1. |

| Harmon, H. R. | 1946 | Memorandum of March 29. USAF Historical Research Center, Reference Division, Maxwell Air Force Base, Microfilm reel 32953. § |

| Johnson, V. B. | 1942 | Memorandum of May 20. USAF Historical Research Center, Reference Division, Maxwell Air Force Base, Microfilm reel 32953. § |

| Kennon, William | 1981 | Transcript of taped interview, recorded for Alan Moore. |

| Panama Canal Department | 1946 | Galapagos: Preliminary Historical Study. Part II (p. 3). |

| 1947 | Galapagos (p. 9). Both in USAF Historical Research Center, Reference Division, Maxwell Air Force Base, Microfilm reel 32958. | |

| Roosevelt, Franklin Delano | 1942 | Letter of March 4 from Dr. Waldo LaSalle Schmitt. |

| 1944 | Memorandum of April 1 to the Secretary of State. Both in Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Box OF 4017: Galápagos Islands. | |

| Schmitt, Waldo LaSalle | 1942 | Diary. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7231: Waldo LaSalle Schmitt Papers, Box 100, Folder 8. |

| Time Magazine | 1946 | Ecuador: Beachhead on the Moon. Issue of July 15. |

| Wetmore, A. | 1942a | Letter of June 5 to Dr. Waldo LaSalle Schmitt. |

| 1942b | Letter of July 7 from Dr. Schmitt. | |

| 1942c | Memorandum of November 20 to Mr. M. L. Leap, Dept. of State. | |

| 1942d | Letter of August 25 from Dr. Schmitt. | |

| 1942e | Letter of December 10 to Mr. Leap. | |

| 1942f | Letter of December 17 from Mr. Leap. | |

| All in Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7006: Alexander Wetmore Papers (unprocessed) Box #90. | ||

§ Contained in deleted section of microfilm 32953, classified FOUO (for official use only), but subsequently released in hard copy (1989) through the Freedom of Information Act. | ||